Australia’s new Part 101 drone regulation amendments came into effect on 29th September 2016. Australian UAV Pty Ltd (AUAV) is of the opinion that these amendments present serious risk implications both for safety and also the viability of this nascent and innovative industry. Senator Nick Xenophon has recognised some of these risks and is moving to disallow these new regulations, so we felt it was a good time to give an update on AUAV’s thoughts on the issue, being one of the country’s larger and more established operators in this sector.

Australia has led the world in drone regulations, with rules in place since 2002. So there is little argument that the regulations for such a fast-moving technology are now due for an overhaul. Much of the work put into the CASR Part 101 amendments is positive, though in their current form cause an unacceptable risk to the public and also to the industry itself in our view. Below we outline the risks and our recommendations for how to move forward with a more balanced and risk-reduced approach.

Risk to Manned Aviation

As the number of drones continues to increase exponentially, it is a statistical near-certainty that we will begin to see collisions with manned aviation, so we need to ensure that we minimise rather than accelerate that risk.

CASA’s current thinking is that a 2kg drone poses little risk to passenger airliners. It is certainly possible that in an unlikely scenario (e.g. striking the rear stabiliser) such a collision could bring down an airliner, but for the most part these aircraft are thankfully engineered to impact things in the sky, given they hit tens of thousands of birds each year around the globe. A rigid drone is different to a soft bird, so will likely cause more damage, but probably still not sufficient to cause a fatal outcome in most cases. However, without any practical testing, nobody can be sure.

The risk to smaller aircraft seems not to have been considered though, and in particular the impact to helicopters in a collision. Unlike airliners, helicopters are not designed to tolerate hitting anything in flight. Their rotor blades are delicate and any object coming in contact with the rear tail rotor has a high likelihood of bringing one down. What’s more, airliners usually fly high above the range of all but the most intrepid drone pilots, whereas helicopters share the sky with drones at low altitudes in busy airspaces such as Sydney Harbour. Unfortunately, Sydney Harbour is, in our opinion, the most likely location for Australia’s first drone vs helicopter incident, particularly as few drone pilots know that this is restricted airspace, and it is such a visually appealing location for aerial photography.

To our knowledge (and we have asked), no empirical testing has taken place in the process of deciding that sub-2kg drones constitute a low risk to helicopters and other manned aviation.

Risk To People On The Ground

Sub-2kg drones, when flown by competent pilots and in respect to all rules, represent little risk to people on the ground. However, as anyone in the industry knows, this category of drone is generally flown by people who don’t have much, if any experience, and are largely unaware of the regulations. So we need to consider the likely impact in realistic terms rather than the idealised scenario of everyone doing just exactly as they should.

In the CASR Part 101 amendments, CASA has effectively communicated that drones weighing less than 2kg are safe for general operation in our society, which is quite a gamble. This may not be the intention but it is certainly the perception from observation of online forums and many discussions with the public at the various meetings and conferences we attend.

Using the Freedom Of Information act, others have questioned CASA on their approach in deeming this weight category as safe, and their 2013 research paper “Human injury model for small unmanned aircraft impacts” was cited as their reference in this regard. This is strange because that paper clearly shows that a 2kg drone flying (or more importantly falling) at the speeds they typically operate at has a 90% chance of causing a fatality if it was to strike a person on the ground below. Their paper shows that a 2kg drone flying faster than just 50km/h is within this threat category, and these drones typically fly and fall at twice that speed, which we have recently demonstrated for the ABC Lateline cameras.

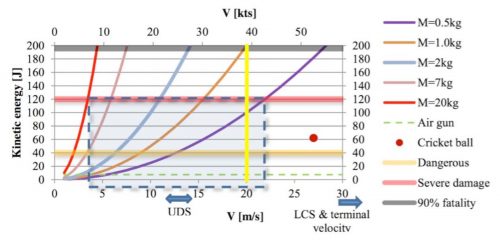

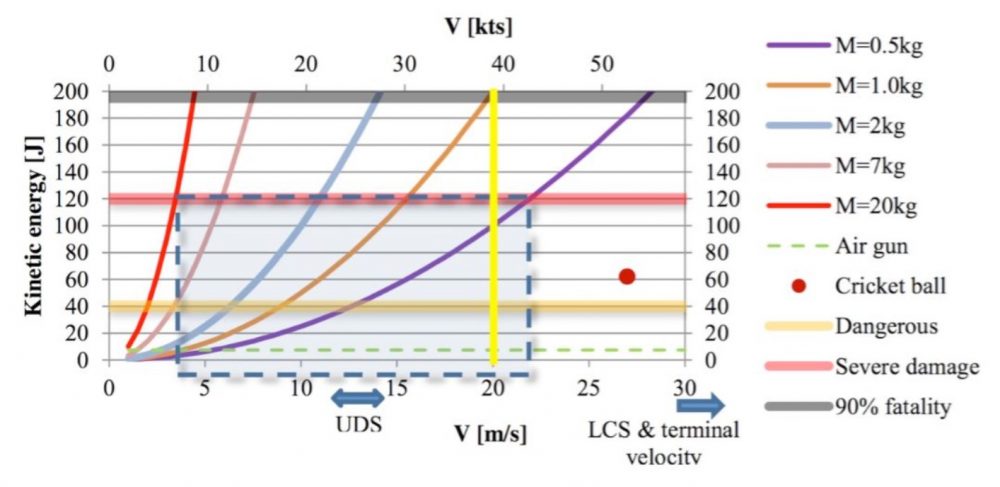

In the graph below you can see the blue line representing a 2kg drone reaches the 90% fatality category at approximately 14m/s velocity (V). In our tests we have shown that these drones fall at between 20 and 30 meters per second (70-100 km/h), so we have added the yellow 20m/s line to CASA’s graph below for clarity. You can see that even a 1kg drone is within the 90% fatality category at these speeds:

I’m sure many in our society would agree, if they were aware, that something which has been determined to have a 90% chance of causing a fatality in the event of an accident should be subject to some degree of licensing and insurance.

AUAV offered to undertake practical testing of the speeds and impact energies in this category for CASA, in collaboration with the CSIRO or other public research organisations in the lead-up to the regulation amendments, but we were not taken up on this.

Risk To Innovation

Innovation has been cited as one of the primary drivers in allowing unlicensed sub-2kg drone operation. However, we feel this is misguided, as the industry requires safety and public confidence in order to gain wider acceptance and an increased commercial appetite for what could be a risky undertaking.

In the same way that we don’t innovate in medical surgery or high-rise construction by bypassing the need for licensing and insurance, the same goes for drones. Without a basic social contract of trust in place, the rate of adoption will be severely hamstrung. Insufficient regulation can lead to accidents and fear, which will effectively put the brakes on future innovation in this space.

Perhaps the most obvious example to relate this to is drone delivery. The public is rightfully very excited at the prospect of drone delivery, and although we feel its realisation on a wide scale is likely to be between 5 and 10 years away, it will eventually happen and when it does it will provide immense savings and efficiency improvements for the entire national economy.

Drone delivery faces a number of obstacles to adoption, some of which are technological (very few, we’re almost there), some are regulatory (easily solved within a few years) but the largest impediment is actually societal acceptance. Few people alive today realise the struggle that the automobile industry underwent to gain this public trust. It took several decades for this dangerous yet attractive new technology (sound familiar?) to be welcomed into our cities and suburbs as an acceptably safe activity. People need to be introduced to potentially dangerous yet beneficial technologies slowly, and we need a safe framework to build their trust upon. It is a long journey, and one which will be slowed severely if drone accidents become a regular appearance in the daily news cycle.

In an industry with an element of danger, we need a foundation of safety upon which we can then innovate.

The other impediment the amendments place upon innovation is that they have effectively turned the lower end of the business into an amateur activity, not able to sustain smaller drone operators which may have some day grown into larger and more capable companies. AUAV started small in 2013, and we eventually grew into a national company undertaking complex projects for multi-nationals and government agencies. As of September 29th 2016, it is no longer possible for small companies doing this more accessible work to thrive and ‘grow up’ into more innovative companies undertaking more challenging projects and generating Intellectual Property. This seems to be in direct opposition to the government’s Innovation Agenda.

Risk To The Industry’s Reputation

From AUAV’s perspective, our biggest concern is the risk to the industry’s reputation. The growth of our business parallels the increasing trust of our clients to utilise this new technology. In the early days we needed to do a lot of work to explain and reassure our customers of our risk management, and after many years of safe operation our industry is now benefitting from that remarkable safety reputation, due in part to the prior regulatory framework.

That perception and commercial appetite suddenly changes when drone accidents are a regular occurrence. Today, our clients are innovative businesses who can perceive the benefits, and the internal advocates are praised within their organisations for suggesting and enabling the use of such technology. When accidents are commonplace those clear benefits will need to be weighed against the risks; risks both for the safety of people on their sites as well as their organisation’s safety reputation, so it might cease to be such a clear choice to use drone technology in future. This could quickly undermine the viability of the whole industry if the incident rate or severity of accidents is high enough.

We feel it is quite a gamble to risk the reputation of the entire professional drone industry to allow unlicensed and uninsured operation in the sub-2kg category, when it is so simple to significantly de-risk this with a basic training and licensing requirement. This is the segment of the industry most likely to see accidents occurring due to their greater numbers and lack of experience, and so should be the focus of increased oversight rather than relaxation.

Finally, there is an unintended effect of increasing the risk appetite within Australia’s licensed drone operators. Operators like AUAV are asked on a daily basis to undertake flight operations which we know to be dangerous or against the rules. Thankfully, as a larger company we have the financial freedom to decline these inquiries, as safety in our business is more important than securing any one project. Smaller operators competing at the lower end of the industry are already known to be taking some of these risks, as they feel pressured to bend the rules to keep money coming in the door and stay afloat. With a sudden influx of competition from people with much lower overheads (no training, no license fees, no insurance, etc) many will be forced to say “yes” to jobs that they know are not entirely safe or legal. Thus the amendments represent both an external risk to the industry’s reputation as well as an internal one from licensed operators having their hands forced on lower safety standards.

Recommendation 1: Training And Basic Remote Pilot License

There is no question that the existing drone regulations involve too much red tape, and we fully agree with reducing that burden. However, we caution against “throwing out the baby with the bathwater”.

The existing regulations require two forms of licensing, a quite rigorous RPA Operator’s Certificate (ReOC) for any business or organisation undertaking drone operations, and also the Remote Pilot Licence (RePL) for the pilot, which can be obtained quite easily by anyone interested by investing just a few days of effort, similar to a boat license.

It is incomprehensible to us that sub-2kg drone operation is being allowed under the proviso of sticking to a very complex set of rules and stipulations, without any form of training or license to ensure that the people are aware of those rules.

Also, as a licensed operator ourselves, we appreciate that one of the largest and most obvious incentives for us to operate safely is the risk of losing that license. If there is no license to lose for bending or breaking the rules, there is little incentive to follow them.

Recommendation 2: Insurance

Professional drone operators typically carry at least $10-$20 million in public liability insurance, and we could list many common scenarios in which damages in this range can be caused by small drone operations. If the operators are not required to carry any insurance, in the event of a serious accident they will not be able to pay themselves, and so those costs will flow to public funds.

CASA has mentioned that through a quirk in the aviation act, they are currently unable to enforce a requirement for sub-2kg drone operators to carry insurance. We feel something needs to change there — if we all agree it is not only mandatory but sensible for everyone driving a motor vehicle to carry 3rd party liability insurance, the same should go for drone operators. Most activities with a degree of public risk in our society require insurance, drones should not slip through the cracks now, or we will surely need to readdress this issue in the years to come when the accidents and resulting law suits begin to build up.

Recommendation 3: Better Communication

There is a great deal of misunderstanding in the public sphere regarding drone regulations in Australia. Most people are unaware such regulations exist, and many who do know are now under the false impression that if your drone weighs less than 2kg you can pretty much do what you like with it. CASA needs to act swiftly and effectively to correct this perception.

We recommend a national media campaign to broadcast the rules, with television and print coverage to get the word out. Previous attempts at education by CASA in this field have been targeted at the demographic interested in drones as a hobby, not to the general public wanting to utilise them as a serious tool for business.

As part of our role on the CASA Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Standards Sub-committee, we described and recommended the creation of a mobile app to integrate up-to-date airspace information with a basic flight permission system. If it met the full scope as suggested, such an app could be a succinct technological solution, solving many of the communication and also enforcement issues at the hobbyist/unlicensed end of the industry. A basic app is planned by CASA, apparently only covering airspace information, but even that is yet to appear despite passing the September 29th date, so people are left with very little information.

One positive move from CASA was to implement an online e-learning module for drone operations, but unfortunately it only skims the surface of the required information. For example if you click through to try learn about restricted airspace it only says “RPA are not permitted to fly within restricted airspace with a conditional status of RA 3” and links to technical data which is unintelligible for anyone lacking training in aviation documentation. Much more is clearly required if we are to expect untrained people to safely operate in this unlicensed category, as I doubt anyone will be able to make the leap from the above information to the realisation that Sydney Harbour is restricted airspace, for example.

Finally, the rules regarding operation in proximity to non-towered aerodromes needs clarifying. Prior to the amendments, licensed operators have only been permitted to fly within 3 nautical miles of an aerodrome if they have a special exemption and stringent safety protocols in place. This is not being communicated as a restriction for the new unlicensed class, which is a very dangerous situation for manned aviation flying smaller aircraft in and out of our regional airports.

In Summary

AUAV commends CASA’s efforts to reduce red tape and improve the drone regulations for everyone, but we feel the current amendments have gone too far and constitute a significant risk to both safety and also the viability of this innovative new industry.

To maintain safe skies for all, AUAV recommends:

- Require training and a Remote Pilot Licence (RePL) for all commercial drone operations.

- Require public liability insurance for all commercial drone operations.

- Vastly improve communication of the regulations to both the public and drone operators.

Until then, we shall continue to cross our fingers that untrained drone operators can fly safely.