Drone delivery is going to be huge.

But it probably isn’t going to be happening as soon as you might think.

As one of the larger drone service providers we do get asked about drone delivery quite often. We did some research and deeper thinking on this as part of a presentation at the Australasian Supply Chain Innovation 2018 conference recently, so thought we would follow through with an article.

When Can I Get My Pizza Delivered By Drone?

Not for a while, but it’s not because we don’t have the technology. From a tech perspective it is already fairly straightforward to deliver packages by drone.

The main obstacles are the current regulations and a lack of societal acceptance in having drones buzzing over everyone’s heads. Also, the numbers don’t currently make sense compared to existing delivery methods unless you’re talking about high-value and high-urgency deliveries (which, I’m sorry, your pizza is not!)

So we will continue to see various highly-publicised trials happening, which can be done under controlled conditions and without any need for it to be economically feasible, but the real drone delivery ecosystem is still a while away. So for now you’ll need to wait those extra few minutes for the delivery scooter instead.

The Many Challenges

Challenges: Technology

Drone technology has advanced at an incredible pace over the past decade, and even consumer-grade drones are capable of following automated flight plans and avoiding obstacles along their way. It is relatively trivial to add a cargo hold to drop things by parachute or descend by delivery line and you have a basic drone delivery system.

So the technology itself is not really what is holding back the timeline for drone delivery, though some tech challenges to be solved or improved along the way are:

- Obstacle avoidance: although current generation consumer drones can avoid crashing into large things like buildings or trees, they aren’t quite up to scratch when it comes to avoiding smaller details like power lines and TV antennas.

- Precise positioning: most drones use non-precision GPS, which will get you within a few metres of your target, but that isn’t quite accurate enough for delivery. RTK GPS is one option for improving this with current technology, as is a visual target (like a QR code) positioned where you want the delivery to be made.

- Certifiably Safe drones: The current regulations are based on the assumption that drones can fail and fall at any moment, which is why you’re not currently allowed to fly overhead or within 30m of people. It will soon make sense for delivery drones to go to the same lengths as manned aviation to guarantee an extremely low likelihood of failure, if the regulatory environment recognises this as a way of allowing them to fly overhead. Obviously delivery won’t be practical in populated areas otherwise.

- Universal Traffic Management (UTM): some serious players are currently working on this including the likes of NASA and the major aviation manufacturers, so it is likely to be solved soon. UTM is an automated traffic control system which will coordinate drones and manned aircraft to operate together in the same airspace while staying out of each other’s way. Think of those science fiction movies where you see streams of flying vehicles automatically cross-crossing their paths above our futuristic cities without any human input. They’re using a UTM.

Challenges: Regulations

Drones operate as part of the wider aviation regulatory framework, which unfortunately moves incredibly slowly, and is already lagging far behind what the technology can safely provide.

The main restrictions with the current regulations are:

- Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS).

- Multiple drones per operator.

- Operation over populous areas.

- Operation in close proximity to people and structures.

Most drone regulations restrict their operation to within sight of their human masters. This is obviously a severe limitation on any drone delivery system, as you might as well deliver the package yourself if you need to follow the drone along its route to keep an eye on it. There are exemptions for this to allow for Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations, but it is currently pretty restrictive and therefore not feasible other than in very remote locations.

The regulations also prevent one pilot from operating multiple drones, which is going to be necessary for any large-scale automated delivery. Amazon would otherwise need a warehouse full of drone pilots next to each one of its delivery hubs.

As mentioned earlier, there are also restrictions around operating in populous areas, in close proximity or overhead people. As the technology matures and everyone gets more comfortable with the low rate of accidents, these regulations should relax.

Challenges: Societal Acceptance

Much larger than the technological or regulatory challenges though is the issue of societal acceptance of drones buzzing around overhead. There is a pretty primal reaction in humans to anything new and unfamiliar, particularly if they feel it could be dangerous to them or their kids playing in the yard. A hovering camera without a human master in sight can understandably trigger this fear reaction.

It will simply take some time for society to get comfortable with drones flying around us, and to see whether the benefits outweigh the risks and perceived nuisance. This same story has played out with many technologies in the past including such familiar things to us now as electricity, cars, satellites, microwave ovens, mobile phones, and so on.

There will always be a small risk (as there still is in those things listed above) and also nuisance factor from noise and visual impact, but when drone delivery moves from a marketing gimmick to a real capability, we will all need to decide whether the pros outweigh the cons. Perhaps drone delivery will only be allowed for good causes, i.e. medical deliveries are ok, but not your burrito.

We will also need to accept yet another form of invasion of privacy, as we’ve seen previously with satellites, CCTV, mobile phones, etc. Drones are packed with cameras and other sensors, so what will the restrictions be on the use and storage of that data? If a drone delivers a pack of beer to you, does the company have the right to the imagery it records of you happily receiving it? What about the 3D scan of your house and yard as it descends? If the Amazon delivery drone sees a Playstation 7 through the window, can they use that to start advertising PS7 games to you? Some of this data will be incredibly valuable, so we need to decide what feels right in allowing it to be captured and used for other purposes.

None of this can be rushed, no matter how much money is poured into a hyped-up marketing machine. Humans are resistant to change if it happens too quickly.

Challenges: Economic

The last major reason why large-scale drone delivery is not here yet, is that it doesn’t currently make economic sense when compared to simpler delivery methods.

There is a lot of hype about quicker delivery of low-cost items like fast food, drinks, and packages from Amazon. These sorts of items can be delivered quite cheaply at present, particularly fast food on delivery bikes cutting through city traffic. The current comparison is between a guy on a bike, being paid what is (with all due respect) probably close to minimum wage, versus an expensive and fragile piece of equipment being operated by highly-paid technicians. The value proposition won’t make sense for this end of the market until we hit massive economies of scale, with the sky dark with drones.

Something often overlooked is the economics of single versus multi-drop deliveries. A drone with a small package is close to its limits of power and endurance, so it isn’t going to be delivering multiple packages in a single flight. Compare this to a delivery van jammed full of packages which can all be delivered along a single planned route, rather than dozens of separate flights out and back.

You also need to allow for the cost of bad actors. This might be at the nuisance level of kids ordering a $5 widget from Amazon and netting themselves a $20,000 drone, it might be the tin-foil-hat brigade or the upset residents of Canberra. No matter their reason, people will be bringing down delivery drones, so they need to be cheap enough that it can be part of the cost of doing business when they do.

Whether it is from deliberate interference or other factors, in the early days losing a drone every 100 flights or so is probably likely, so the drone can be amortised at something like $200 per flight. If the drone survives longer than that, the lithium batteries and small brushless electric motors have a maximum lifespan of a few hundred flight hours, so are expensive parts which need to be accounted for as consumables, as well as the work in replacing and maintaining them. So even though there’s nobody on board and most of it can be entirely automated, drone flights are far from free.

Niche Applications

So we won’t be getting our dinner delivered by drone any time soon, but there are some areas we will see this technology begin to gain traction.

Prisons are unfortunately one of the early launch customers for drone delivery. Authorities around the world are struggling with how to keep drugs, mobile phones and other nefarious tools of the trade from being delivered to inmates, as seen in this video from a London jail.

In more commercial terms though, the early successes will be in niche cases where the regulations and societal impact are much less of an issue, such as:

- Ship-to-shore, or deliveries between islands and the mainland coast.

- Across geographic boundaries such as rivers and gorges, or political boundaries.

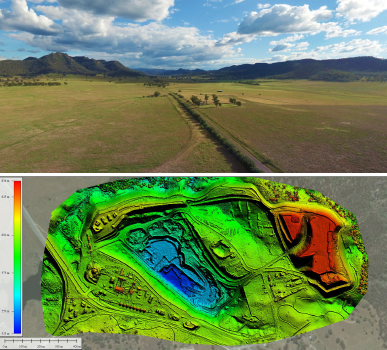

- Critical items such as machine parts to remote work sites like mines and farms.

In terms of the types of items most suited to the pioneering days of drone delivery, think of things which have a very high value through an urgent need, but a low replacement cost if things go wrong. Examples would be documents, lost keys and pathology samples, not Fabergé eggs.

The most obvious candidate here is medical delivery. Getting vaccines, transplants, an EpiPen or defibrillator to someone in need is something I think everyone can accept despite the buzzing nuisance and very remote risk of it dropping on you along the way. This will hopefully be an excluded case to cut through the regulatory issues in the near future, and by the technology proving itself in this area it will allow more commercial use to follow through in its wake.

Developing Nations: Leapfrogging the West

A final thought is that developing regions are likely to lead the West when it comes to drone delivery (and also passenger drones, but that is another story).

These areas generally have a more flexible regulatory environment, and are able to make swifter policy changes to accommodate such a promising new technology.

The benefits are also proportionally much greater, given a lack of traditional delivery infrastructure. For a westerner forced to wait a few agonising minutes for their takeout to arrive, this is literally a “First World Problem”, whereas to get potentially life-saving packages through to people where there are no roads. or across areas unsafe to travel can dramatically change lives for the better.

Zipline for example is already making a success of such a service in Rwanda with their rugged fixed-wing drones.

A Likely Timeline

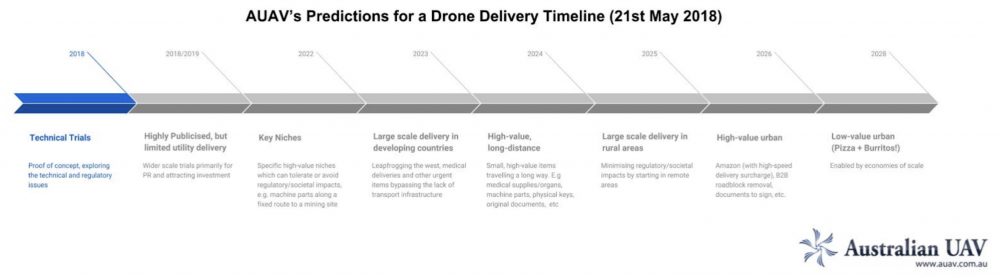

Ok, time to place our bets, this is how we see it all panning out over the next 10 years:

- 2018: Early Trials

Continuing proof of concept trials, exploring the technical and regulatory issues. - 2019: Highly-Publicised, but Limited Utility

Wider scale trials primarily for PR and to attract investment. - 2021/22: Success in Key Niche Areas

Specific high-value niches which can tolerate or avoid regulatory and societal impacts, e.g. machine parts from regional towns out to mining sites. - 2023: Large Scale Delivery in Developing Nations

Leapfrogging the West, medical deliveries and other urgent items, bypassing the lack of traditional transport infrastructure - 2024: High-Value, Long-Distance Deliveries in the West

Small, urgent items travelling a long way, e.g. medical supplies, keys, documents, repair parts, etc - 2025: Large-Scale Delivery in Rural Areas

Minimising regulatory/societal impacts by larger scale services starting in remote areas - 2026: High-Value Urban

Amazon and Co with a paid high-speed delivery option, B2B and government process optimisation, commercially critical deliveries - 2028: Low-Value Urban (pizzas and burritos!)

Enabled by economies of scale brought about by earlier phases.

In Summary

We agree with the hype that drone delivery is going to be a huge industry, massively disruptive to traditional logistics services, and a great benefit to society.

It is, however, further away than what most people think.

We will enjoy watching it unfold and may even jump in when the time is right. By the time drone delivery is ready for prime time, AUAV will have locations in every major town across in the country, which will make a pretty good foundation on which to roll out such services.